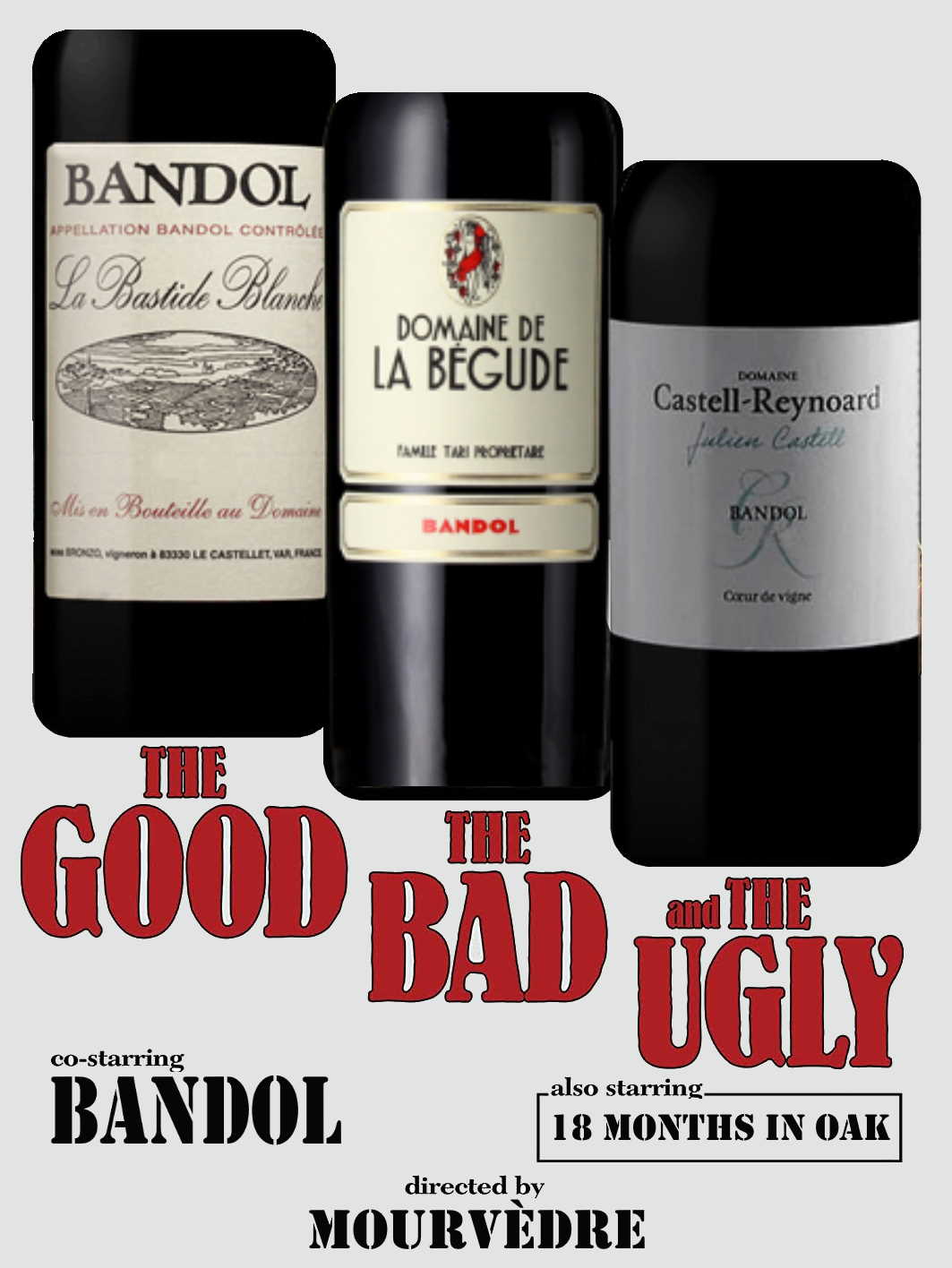

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Bandol

I don't remember the last time I mentioned Bandol without someone bringing up its wine politics. Everything is portrayed as new-versus-old and tradition-versus-innovation, and just as much as good-versus-bad, especially the people behind the philosophies. In these charged political conversations, two estates are mentioned somewhat more than others - Bastide Blanche, accused of dragging their heels and refusing to move with the times, and Bégude, accused of destroying the appellation by throwing tradition away too quickly.

One of those two producers is even bottling their latest, newest cuvée with no oak whatsoever, as a Vin de France. They're oaking their new rosé, sell the 2018 rosé as the current vintage and even have a concrete egg lurking in the cellar. They make fantastic, age-worthy single-parcel reds. They're organic and are taking practical steps towards biodynamic and environmentally conscious viticulture.

Can you guess which of the two producers this one is?

The other producer is bottling their newest cuvée, 100% Mourvedre, with no aok whatsoever, as an IGP Med. Their rosé is dark and 2019 is the current vintage. Both reds and whites spend time in amphora. They make fantastic, age-worthy single-parcel reds. They're organic and are taking practical steps towards biodynamic and environmentally conscious viticulture.

Now, guess again - which is which?

Let me throw a spanner in the works by introducing Producer Number 3. Producer Number 3 is more of a pariah through their actions than their politics, unlike the other two. They do, however, also oak their rosé, play around with single-variety IGP Med reds, and make fantastic, age-worthy single-parcel reds. They're organic and take a practical but ambitious approach towards biodynamic and environmentally conscious viticulture.

I hope a pattern is now evident.

Dig a bit deeper, and the cracks distinguishing these producers do, of course, widen. One of the producers keeps their 'new' cuvées distinct from their traditional ones with an overhauled, modern label (Bastide Blanche's 'Contrechamps', or 'counter-field'), while another minimises the differences.

Domaine de la Bégude Thyrsus 2020

Domaine de la Bastide Blanche Contrechamps 2019

The brand of environmentally-friendly agriculture varies of course from 'practical' to 'cautiously enthusiastic', to downright 'regenerative'. The vines are different even to the untrained eye in the vineyard, with varying levels of groundcover, different training methods, and most evidently even in the way they fit into the landscape.

It's also worth pointing out that these three aren't making wines in total isolation - the 60-odd other producers in Bandol are of course experimenting in similar directions, often with oaky rosés as Vins de France or single-variety cuvées. I don't know enough about the intricacies of these other producers, but I am certain that, from an outside perspective at least, they are all actually surprisingly similar.

Anyone who reads what I write with any regularity will know that I am a big believer in appellation reshuffles. Other than the rebranding of Bandol as a 'Cru de Provence' or effectively making it a village-level Provence sub-appellation (which I think would be good for everyone, not least of all by offering a choice), I think Bandol is in desperate need of quality tiers to its appellation.

I do not believe in appellation systems. They constrain, restrict choices, stifle freedom, and confuse consumers. If, however, they are to be kept, they must either be so flexible as to be meaningless, or be specific enough that most decisions fit neatly into an appellation that wholeheartedly welcomes them.

Bandol AOP currently requires 18 months of barrel ageing before release. A recently voted-upon proposal suggests reducing this to only 12 months, albeit with the remaining six months in bottle I believe. A key argument of course is that this is only a minimum, and that producers who believe in this extended barrel ageing can opt for it.

The counter argument however is that most producers will stick to the bare minimum. 'Good' producers will be dragged down, and poor, uneducated, ill-informed consumers will suddenly lose the protection and quality that the appellation has decided for them. How, therefore, can producers who hold themselves to a higher standard demarcate themselves from producers who want greater freedom in the cellar?

There is no need to reinvent the wheel here. Wine regions across the world have grappled with similar problems for decades, if not centuries. "Classico", "Crianza", "Supérieur/Superiore", "Riserva" and "Gran Riserva" are just some of the solutions that suit so many wine producers.

(on this note, I believe that St Émilion Grand Cru is primarily vinification and viticulture-driven rather than terroir, but was told otherwise by an expert the other day, so I'm no longer certain. If I was correct, then we can add Grand Cru to the list of style - rather than terroir - attributes)

Of course, as so many of these unusually un-oaked wines suggest, quality is not at stake here. Style is. Perhaps a 'Classico' variant would be more suitable than a 'Superiore', although given Mourvedre's demanding nature and love of the sun, maybe both Classico and Superiore (based on ripeness and alcohol levels) attributes would be relevant here.

I would love to see "Bandol Grande Réserve" (or "Grand Vin de Bandol" vs "Vin de Bandol") as an option for wines that have spent 36 months in oak as a way of going above and beyond what is currently on offer - so much of the debate seems to be focussing on less regulation that we're perhaps forgetting the need or desire for further regulated terms to match the wide variety of styles. If the syndicat cannot be brought on board with this, perhaps a private initiative akin to Germany's VDP GW wines?

Of course, as I mentioned, both of these (and indeed the majority of Bandol producers) produce single-parcel (or as close to single-parcel as is possible with a blended wine) wines. La Brulade, Fontanéou and Estagnol, Clos Castell... all are from very limited areas, with care and attention lavished on them, and it shows. They age well, better in fact than their regular Bandols. Is it time to implement a terroir-driven "Bandol Grand Cru", and include within it a 24 or 30 month oak requirement?

The issue is that all of these terms refer to more stringent requirements, rather than less so. The onus is on those ageing longer to prove it, rather than those ageing less to admit it. Perhaps "Bandol" should be kept as it is, and those wishing to age less in oak and more in bottle could settle for "Bandol Hors Bois".

Of course, much of this arguing is about the reds, which despite their traditional dominance are today a minority in Bandol. Rosé, by far the big volumes player with somewhere in the region of 80% of production, is going from commercial strength to strength, and quality... downhill. Bandol rose to rosé prominence (sorry) as a Provencal pink with weight, structure, and rich ageing potential potential from its Mourvedre backbone. Today, it's a pale Provence imitation, rarely aged, and increasingly lightweight, made with Grenache and Cinsault, and the odd bad plot of Mourvedre chucked in.

A small handful of producers is pushing back against this, and returning to Bandol's high-end rosé roots, with darker colours, more intensity, proper depth, and even the occasional oak. The syndicat usually refuses them the AOP. I know of only one other appellation where the traditional rosés are now forbidden, Bardolino Chiaretto, whose wines I would avoid without question since the changes. It's not a good reputation. Given the whole brouhaha about Bandol being an appellation proud of its long oak-ageing, I don't think it's a good idea to ban it for 80% of wines produced there...

This is especially relevant when considering Mourvedre's reputation for late ripening and reductive tendencies. Young, pale rosé is all-too-often prone to reduction and sulphury whiffs, especially in regions still finding their feet in a pale rosé world. Young, pale rosé is equally prone to blandness and absence of fruit, which crisp, barely-ripe Mourvedre doesn't help with. Harvesting riper and vinifying/ageing in an oxidative environment is an obvious one - and Bandol has understood that for the reds. When too for its rosés?

Domaine de la Bastide Blanche oaked rosé (tank sample, as yet unreleased and unnamed) 2020

Domaine Castell-Reynoard For my Dad rosé 2019

Domaine de la Bégude Irréductible 2019

For good measure, I'm including two other non-Bandol oaked Mourvedre rosés Elizabeth Gabay MW, Guillaume Tari and I tasted with these other Bandol ones.

Chateau l'Ermite d'Auzan 2019

Famille Fabre les Amouries

Rather than reject these traditional flagship quality rosés, Bandol should stop fighting itself and recognise that these are the wines that will bring it to 21st century relevance and renewed prosperity - not unoaked Mourvedre red or oaky behemoths on either side of the extreme - just well-made, high-end, commercially relevant rosés that consumers and trade have already expressed an interest in.

As with the reds, there is no easy solution that will please everyone. Enforcing or encouraging this in the cahier des charges will simply result in more strife, especialy from the smaller and less prosperous producers who have relied on the rosé bubble for a few more years of positive cashflow. As with the reds, I suspect that the best option would be a 'superior' designation, perhaps "Bandol Rosé de Réserve" or something - but the least they can do, if encouraging it is too much, is not ban these wines.

From a practical point of view however, none of these will happen. IGP Med and Vin de France will continue to be the designation of choice for interesting, innovative wines, red and rosé. Bandol AOP will continue to be prized by consumers who care primarily about the appellation name on the label rather than the wine inside and the story behind it, leaving Contrechamps, Thyrsus, and Irréductible not-so-well-kept secrets for wine-lovers, not -snobs.